by Catherine G. Wolf, Ph.D. on Wed, 2013-11-06 09:35

Article Highlights:

- Cathy Wolf of Katonah, N.Y., has had ALS for 18 years and has lost nearly all voluntary movement, including speaking ability.

- Wolf has been testing brain-computer interface (BCI) systems and assisting with their development since 2006.

- BCIs that are well along in development either sense brain activity through the scalp or through electrodes implanted into the motor cortex of the brain. They show promise in restoring a user's ability to communicate and perform various actions.

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) enable a person with no voluntary movement to communicate, surf the Web, write emails, and even move a wheelchair. For people with advanced ALS, spinal cord injuries, stroke or other neuromuscular conditions, BCIs promise to give them back the world.

There are no commercially available BCIs yet. But pilot studies in users’ homes are in progress to find out how to make these systems easy to use for both the user and the caregiver.

A user-interface expert

I have had ALS for 18 years. In that time, I’ve lost the ability to move my arms and legs, eat by mouth, speak and even breathe. I do have some movement in my face. But ALS is unpredictable. I might lose the small movement of my eyebrows and mouth in the next six months or the next year.

|

|

|

|

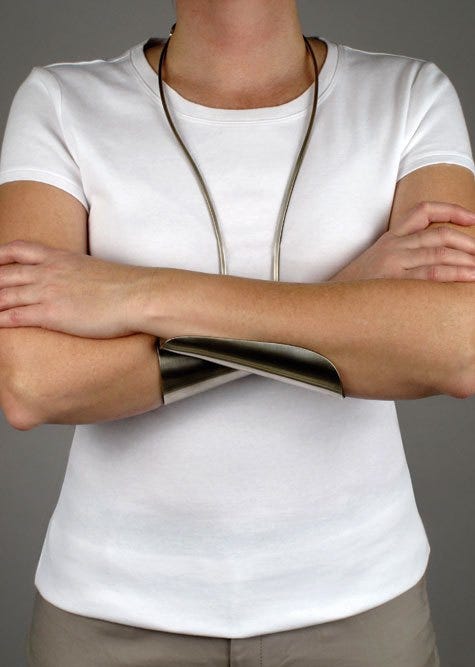

| Wearing an electrode cap containing conductive gel in the electrode spaces, Cathy Wolf operates her computer by paying attention to single characters or function shortcuts on the monitor. |

I have been

participating in the Wadsworth Center’s development of BCIs since 2006 (the center is part of the New York State Department of Health). I serve as a user and also the user-interface expert because of my long history in human-computer interaction at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center.

I am not yet dependent on the BCI. For now, I am using an infrared switch which I activate by raising my eyebrows to select letters and words from an onscreen scanning keyboard. This method is currently faster than the BCI. I participate in the research both for myself and others with movement disorders.

Wadsworth BCI picks up brain waves through the scalp

The Wadsworth BCI is based on electroencephalogram (EEG) signals picked up from the surface of my scalp. I wear an eight-channel electrode cap with electrode gel on my scalp. The signals are sent to an amplifier and then to a computer.

When I started my participation with the Wadsworth Center, the only application available was typing and then hearing back what I had typed in text-to-speech, the mechanical voice in which computers speak.

Since then, many improvements and applications have been added.

P300: The 'a-ha' response

On a large screen, I look at a matrix of quickly flashing letters and symbols that flash in a quasi-random, but known, order. My task is to count the number of times the symbol I want flashes. The computer is looking for a component of brain waves called P300. The P300 response is often called the “a-ha” response because it occurs about 300 milliseconds after someone sees something significant. The computer uses an algorithm to pick the symbol with the highest P300 amplitude.

Word prediction

One improvement in the Wadsworth BCI system is word prediction. Word prediction is based on the frequency of the next letter, given the preceding letter. For example, if I type “w,” the words “when, was, with, we, who” would be listed. If the desired word is on the list, I pick it, instead of typing the entire word. There is also next-word prediction based on the previous word. These changes increase speed and accuracy.

The Wadsworth researchers also experimented with different flashing patterns. One had seven different colors for the symbols in the matrix, and I was instructed to name the colors of the desired symbol. In an independent study with seven people who had ALS, the use of color seemed to increase accuracy.

Email

Another, and more important, BCI application was email. I can email anyone, and there is a feature for remembering recent email addresses. I often email members of the project with suggestions about the user interface, and other suggestions.

Rich site summaries

There is also a Web application based on RSS (rich site summary) feeds. I can read The New York Times, ALS news, and even listen to music on Pandora.com. There is a YouTube application in which you type a subject matter, like the Beatles or cats, and you get a list of YouTube videos on the subject. There’s also a picture viewer application.

My recommendation: Caregiver alerts

I noticed that when I am using BCI, my caregivers sometimes occupy themselves with other things. I suggested adding the ability to call my caregiver or announce a problem with the ventilator. These messages are repeated until someone comes to turn them off. The messages can be customized.

My recommendation: Adding mouse 'emulation'

For all the BCI-specific applications, there are always several that were not included. So at the Users’ Forum at the

Fifth International Brain-Computer Interface Meeting in June 2013, in which I was a remote participant, I said my ideal BCI would work with any computer or Internet application, just as my scanning keyboard and switch can be used. This would require adding mouse emulation [imitation] to the Wadsworth BCI, but some BCIs already have the ability to move the mouse.

BCIs in the pipeline

At the same meeting, in the session called “BCIs for Users with Impairments,” a variety of modalities was presented:

- Auditory binary choice (two choices) BCI: The user is asked a yes/no question while in one ear “yes” is repeated and in the other ear “no” is repeated. Randomly, “yep” replaces “yes” and “nope” replaces “no.” The user answers the question by either counting the number of yeps or nopes.

- Visual binary choice BCI used with the eyes closed: The user is fitted with special glasses which contain LEDs flickering at different frequencies in each eye. The LEDs can be seen with the eyes closed. The user answers a yes/no question by attending to the appropriate eye.

- Visual BCI that uses eye blink in addition to EEG: Eye blink is detected by a different brain response.

Although these were laboratory experiments, not for home use, I am sure the goal is to move them out of the lab. Thus, if you have movement disabilities, there is likely to be a BCI in the works that meets your personal needs!

The iBrain may monitor sleep but can't steal thoughts

Then there is the

NeuroVigil’s iBrain, a one-channel dry electrode mounted on a headband that picks up EEG. The only application listed on the company’s website is in-home sleep monitoring, but the iBrain has been recently touted as

“hacking” into the mind of Stephen Hawking and another person with ALS, Augie Nieto (co-chair of MDA’s ALS Division).

The iBrain was used to pick up brain waves when they thought of moving their left or right hands. Curious about the iBrain, I sent email twice to NeuroVigil. I got no response.

The word “hacking” connotes unauthorized access. When applied to the mind, it implies unauthorized access to one’s thoughts.

I don’t know whether the iBrain could function as a BCI. But I want to reassure everyone that the iBrain or any BCI cannot read your thoughts. BCIs require conscious effort to work. Counting how many times a symbol flashes is hard work. There is no way these systems could steal your thoughts.

As to whether the iBrain could function as a BCI, I suggest you wait for studies in peer-reviewed journals, and not be swayed by demonstrations.

BrainGate: An implanted BCI

Another approach to BCIs is illustrated by the

BrainGate Neural Interface System. In such systems, explained neurologist Leigh Hochberg, a sensor is implanted on the surface of the motor cortex of the brain, in an area about 4 millimeters by 4 millimeters.

Once the sensor is implanted, the user imagines moving a limb, often the arm or hand. The sensor transmits the electrical signal to a decoder (one or more computers and software) that turns the brain signals into a useful form for an external device. The external device may be a computer with a cursor, a prosthetic device, a robotic arm or a device that controls the environment [such as the temperature in the room]. The recording is done intracranially [inside the skull] and is called

electrocorticography (ECoG).

“My personal goal — shared by our BrainGate team — is to develop systems that provide a person with advanced ALS, or locked-in syndrome from brainstem stroke, or traumatic brain injury or other disorders, with 24-hour-a-day continuous point-and-click control over a computer cursor, enabling that person to communicate readily and to use any software on any computer that could be controlled with a point-and-click,” said Hochberg.

Implanted devices are potentially more natural for performing complex actions, especially when recording from several brain locations. One goal is to eventually use implanted intracranial devices like the BrainGate to bridge the nonfunctional motor neurons in people with conditions such as advanced ALS, brainstem stroke or spinal cord injuries, allowing them to move their own limbs.

The field is in its infancy, Hochberg noted. Still, there have been impressive advances. Three test users with quadriplegia were able to use the BrainGate to operate either a prosthetic arm or a three-dimensional robotic arm to reach and grasp. One tester used the BrainGate system for more than five years. After five years, the signals from the array were still useful to control external devices, though not as robust as the first year. This is significant because it shows that the BrainGate could provide use over a “clinically valuable time period,” Hochberg said.

Interestingly, implanted ECoG systems may make the noninvasive EEG systems more accurate. At the recent BCI meeting, a paper was presented about the successful use of ECoG to predict EEG in six people.

Although the goal of intracranial systems like the BrainGate is to seamlessly turn thoughts into movement, there is no danger that private thoughts could be stolen. Such systems reside in the motor cortex, not the area where complex thoughts and planning take place.

While some people may prefer the convenience of implanted systems, others are concerned about the risks.

Restoring abilities

The advances in both EEG and ECoG systems can now give people with no movement the ability to speak, the most human ability, and for me the most important.

Already, in pilot projects, they are enabling paralyzed people to use computers and control the environment. It is my hope that such systems will soon be available to all who need them.

For an in-depth look at the state of BCI science, see a

summary of the Fifth International Brain Computer Interface Meeting sessions, with links to research articles.

Cathy Wolf, 66, earned a doctorate in psychology from Brown University in Providence, R.I., after which she began work in the field of human-computer interaction. At the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., she worked on speech and handwriting recognition and natural conversational interfaces, registering nearly a dozen patents.

In fall 1997, Wolf learned she had developed ALS. Since then, management of the disease has included a tracheostomy, a ventilator and a feeding tube. Unable to speak, Wolf communicates with her husband Joel and the rest of the world using a WiViK onscreen keyboard; E-triloquist speech program software; and a SCATIR switch that works through detection of a reflected beam of light and which she operates with her eyebrows.

In addition to writing for the MDA/ALS Newsmagazine and American Academy of Neurology’s magazine Neurology Now, Wolf is an amateur poet and has published two poems in peer-reviewed journals. She was profiled in the January 2007 issue of the MDA/ALS Newsmagazine.